Dian Fossey’s Legacy in Gorilla Conservation

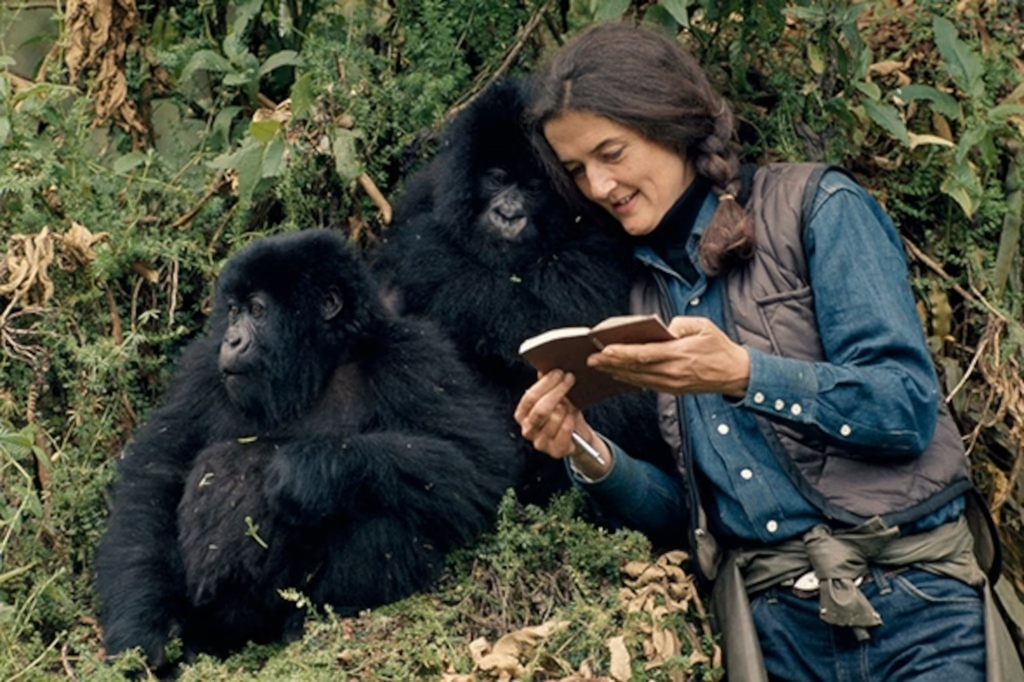

Dian Fossey’s legacy in gorilla conservation is complex, powerful, and impossible to separate from the survival of mountain gorillas today. Long before gorilla trekking permits, luxury eco-lodges, or global conservation campaigns existed, Fossey chose to live among the gorillas of the Virunga Mountains and dedicate her life to their protection. Her work reshaped how the world understands gorillas and forced conservation to confront uncomfortable truths about exploitation, poaching, and human responsibility.

Her legacy still shapes every gorilla encounter in East and Central Africa.

Entering the Virungas: A Radical Commitment

When Dian Fossey arrived in Rwanda in the late 1960s, mountain gorillas stood on the edge of extinction. Poaching, habitat loss, and lack of global awareness had pushed their numbers dangerously low. Fossey did not approach conservation from a distance. She lived in the forest, endured isolation, harsh weather, and constant danger, and committed herself fully to studying gorillas on their own terms.

She established the Karisoke Research Center between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke, embedding research directly within gorilla habitat. This decision allowed long-term observation and built the foundation for modern gorilla science.

Changing How the World Sees Gorillas

Before Fossey’s work, gorillas were widely misunderstood. Popular culture portrayed them as violent, aggressive creatures. Fossey’s research revealed a very different reality. Through years of close observation, she documented gorilla social structures, communication, parenting, and emotional depth.

Her findings humanized gorillas without romanticizing them. She showed them as intelligent, gentle, and socially complex animals. This shift in perception proved crucial. People protect what they understand. Fossey gave the world a reason to care.

That change in narrative remains one of her most enduring contributions.

Confronting Poaching Head-On

Fossey’s conservation approach was confrontational and uncompromising. She actively opposed poaching networks operating in the Virungas and saw firsthand the devastating impact of snares and illegal killings. The murder of Digit, a silverback she had closely studied, marked a turning point in her work and hardened her resolve.

She believed that gorillas needed absolute protection, even if it meant conflict with local interests and authorities. Her methods sparked controversy, both during her life and after her death. Yet they forced global attention onto the realities of wildlife crime and the urgency of enforcement.

Modern anti-poaching strategies owe much to this early, uncomfortable spotlight.

Building the Foundations of Modern Gorilla Conservation

Today’s gorilla conservation model rests on pillars that Fossey helped establish. Long-term research, individual identification of gorillas, daily monitoring, and the recognition of gorilla families as social units all stem from her work.

These practices now underpin conservation efforts in Volcanoes National Park, Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, and Virunga National Park. Rangers and researchers still rely on techniques developed during Fossey’s time to track gorillas, monitor health, and intervene when necessary.

Her influence lives on in daily fieldwork, not just history books.

Tourism as an Unintended but Powerful Outcome

Dian Fossey herself opposed gorilla tourism, fearing it would harm the animals she fought to protect. Ironically, carefully managed tourism has become one of the strongest tools for gorilla survival.

What tourism adopted from Fossey’s legacy is restraint. Limited visitor numbers, strict rules, minimum distance guidelines, and health protocols all echo her insistence on prioritizing gorilla welfare over human access.

Without her foundational work proving that gorillas could be habituated safely and studied closely, regulated tourism would not exist today.

Community Inclusion: Where the Legacy Evolved

One area where conservation evolved beyond Fossey’s original approach is community involvement. Early conservation focused heavily on protection without adequately addressing local livelihoods. Over time, lessons learned from conflict led to a more inclusive model.

Today, communities living near gorilla parks benefit directly from tourism revenue, employment, and development projects. This evolution strengthened conservation outcomes while maintaining Fossey’s core principle: gorillas must be protected at all costs.

Her legacy did not remain static. It adapted.

A Legacy Marked by Sacrifice

Fossey paid a heavy personal price for her work. She lived under constant threat and was murdered in 1985 under circumstances that remain unresolved. Her death shocked the world and cemented her status as one of conservation’s most polarizing figures.

Yet her sacrifice amplified global attention on gorilla conservation. Donations increased. International support strengthened. The urgency she lived by became impossible to ignore. Her death did not end her mission. It expanded it.

Why Dian Fossey Still Matters Today

Mountain gorilla populations have grown cautiously since Fossey’s time, a rare conservation success story. This recovery reflects decades of effort rooted in her research, advocacy, and uncompromising belief that gorillas deserved protection.

Every gorilla trek today carries echoes of her work. Every ranger patrol, research report, and conservation policy traces part of its lineage back to Karisoke.Her legacy reminds us that conservation requires courage, persistence, and a willingness to stand alone when necessary.

Final Reflection

Dian Fossey’s legacy is not simple, comfortable, or universally admired. It is powerful because it forced change. She challenged how humans relate to wildlife and demanded accountability when gorillas had no voice.

Gorilla conservation in East and Central Africa exists today because someone once chose to stay in the forest, speak for the animals, and refuse to look away.That choice continues to protect gorillas long after her voice fell silent.